Homily 5 - Forgive Us Our Debts As We Forgive Our Debtors. And Lead Us Not Into Temptation, But Deliver Us From The Evil One.

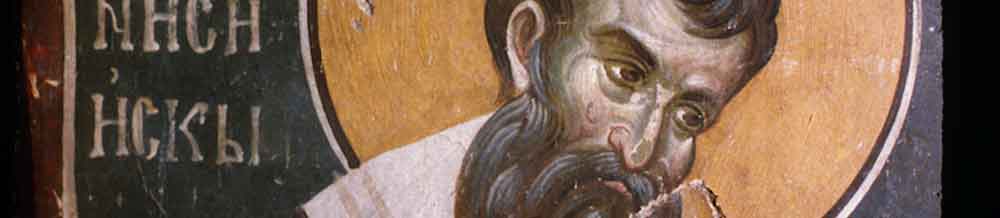

Saint Gregory of NyssaTrans. Theodore G. Stylianopoulos, 2003

Download pdf

Becoming Like God

Our discourse has come to the pinnacle of virtue. The words of the prayer now trace the profile of a person who would approach God. Such a person would no longer seem to be within the realm of human nature but one who, through virtue, would be likened to God Himself. He would appear to be an- other god doing those things which only God can properly do. For the forgiveness of debts is a unique and special prerogative of God. It was said: "No one can forgive sins but God alone" (Mk 2:7). If then a person seeks to imitate in one's own life the attributes of the Divine Nature, he becomes in some way that which he manifestly imitates through action.

What does Christ therefore teach us? First, that we should acquire spiritual boldness through good works and then request that God be forgetful of whatever offenses we have committed. He tells us through these words that the Benefactor is properly approached by one who is a benefactor, the Good by one who is good, the Just by one who is just, the Forbearing by one who is forbearing, the Loving by one who is loving. Similarly in all other cases, a person obtains confidence in prayer by willingly imitating every conceivable attribute of God who is both kind and gentle, the source of all blessings and the dis- penser of mercies to all.

It is not becoming that an evil person should enjoy intimacy with a good person, nor that a per- son who wallows in impure thoughts should have communion with one who is pure and undefiled. In like manner, hardness of heart separates the supplicant from the love of God. Whoever holds someone else in bitter bondage because of outstanding debts has by his own conduct excluded himself from divine love.

What communion can there be between love and cruelty, kindness and harshness, or any attrib- ute and its opposite that is evil? Mutual opposition keeps them separated. For whoever is possessed by any particular attribute is necessarily estranged from its opposite. Just as one who dies no longer lives, and the one who lives is estranged from death, so also he who approaches the love of God must neces- sarily be removed from every disposition of callousness. Whoever is free of all those dispositions under- stood as being evil, he becomes in some way god by reason of his condition having achieved in himself what reason understands to be attributes of God.

Do you see to what greatness the Lord exalts those who hear Him through the words of the prayer? He transforms human nature in some way to be closer to the divine. He decrees that those who approach God should become gods. Why do you come to God, He says, in a slavish manner, trembling in fear and plagued by your own conscience? Why do you exclude yourself from the confidence which coexists with the freedom of the soul from the beginning and which is intrinsic to the essence of your nature? Why do you use flattery with Him who cannot be flattered? Why do you direct fawning and flat- tering words to the One who looks at deeds?

Every blessing that comes from God is permissible to you. You can possess it with a free spirit. Be your own judge. Cast the saving vote for yourself. Do you ask God to forgive your debts? Forgive the debts of others and God will cast his favorable ballot. You yourself are the lord of judgment concerning your neighbor. This judgment, whatever it maybe, will bring an equal decision upon you. For whatever you decide to do, will be ratified by the divine judgment in your case, too.

Being Examples of God

How could then anyone worthily expound the noble meaning of the divine utterance? Mere ver- bal explanations are not adequate to invoking the words, "Forgive us our debts as we also have forgiven those indebted to us." The thoughts that come to mind about this petition seem bold to me even to ponder. It is even more daring to try to express their meaning with mere words.

What I am really saying is but this: Just as God is an example to those who achieve goodness and seek to imitate Him according to the Apostle's words, "Be imitators of me, as I am of Christ" (I Cor 11:1), so conversely God wants your disposition toward the good to be an example to Him! The order of things is somehow reversed! I dare propose that, just as the good is accomplished in us by imitating God, so also it is hoped that God himself will imitate our own deeds whenever we achieve anything good.

Accordingly, you yourself can say to God: Do that which I have done. Lord, although You are the King of the universe, imitate Your servant, who is a poor beggar. I have forgiven the debts of others; do not Yourself cast away Your supplicant. I have sent away my debtor rejoicing; let Your debtor also depart in like manner. Do not make Your debtor sadder than I have made mine. Let both be equally grateful to their creditors. Let both of us ratify the same forgiveness to our debtors, Yours and mine. My debtor is so and so. Your debtor is myself. Whatever judgment I have passed over him, let Your judgment be the same over me. I have absolved, so also absolve. I have forgiven, so also forgive. I have shown much mercy to my fellow human being. Lord, imitate the mercy of Your servant.

But my offenses against You are graver than those of my neighbor against me. I fully acknowl- edge this. Yet be mindful of how much You excel in goodness. You prove Your justice when You grant mercy to us sinners in proportion to Your exalted power. I have shown little love because my nature was capable of no more. But You can show as much love as You want because Your generosity is not cur- tailed by any lack of power.

Our Debts to God

Now let us ponder in greater detail how the present petition of the prayer applies to our human condition. It may well be that, through reflection on its meaning, we will be guided to a loftier way of life. Let us then examine what are the debts owed by human nature and again those things that lie within our own authority to forgive. For knowledge of these matters will give us a measure of insight into the high nature of divine blessings. Let us therefore begin by outlining the hum~in debts to God.

The first penalty that man is obliged to pay to God is that he has revolted from His Creator and has defected to the adversary. Man became a deserter and apostate from his natural Lord. Second, lie exchanged the liberty of free will with the wretched slavery of sin. Instead of communion with God, he preferred the tyranny of the power of corruption. What evil could be considered second to forfeiting the vision of the Creator's beauty and turning one's face toward the shame of sin? What degree of penalty can be set for showing contempt for divine blessings and preferring the enticements of the evil one? Consider all the offenses against God that we can find in Scripture and can contemplate ourselves. For example, the defacing of the image and the corruption of the divine character stamped in us at the time of creation. Or think of the loss of the valued coin (Lk 15:8-9). Or consider the abandonment of the Fa- ther's table, the fall into the foul-smelling life of the swine and the corruption of the precious wealth (Lk 15:12-15). What discourse can enumerate all these offenses?

For all these things the human race is guilty before God and liable to pay the full penalty. It is for this reason, I think, that the Divine Word seeks to train us through the prayer. He teaches us never to be overly bold in our entreaties before God, as if we possessed a pure conscience, even if we are removed from human offenses to the highest degree.

Perhaps someone can stake a claim on such grounds and boast about his conduct as did that rich young man who was trained in life to observe the commandments (Mk 10:17-22). He might say to God, "All these I have observed from my youth" (Mk 10:20), and think that because he has transgressed none of the commandments, he should not properly ask for forgiveness, since the plea for forgiveness is appropriate only to those who have sinned. He could affirm the same about those who have been defiled by fornication, or that entreaty for forgiveness is necessary for those who have committed idolatry be- cause of greed. And in general it is good and proper to take refuge in God's mercy by all who have stained the soul's conscience by some offense. But if he be like the great Elijah, or like him "among those born of women" (Mt 11:11) who came "in the spirit and power of Elijah" (Lk 1:17), or like Peter or Paul or John or some other of the great figures testified by Scripture–why should he offer the prayer ask- ing for the forgiveness of debts? Why, if he has incurred no debt of sin?

No one should be of this mind and exhibit the audacity of the Pharisee (Lk 18:10-42). The Phari- see did not know what he was by nature. For if he had understood that he was human, he would have been taught by Holy Scripture that human nature is in no way free from defilement. Scripture says: "It is not possible to live one day without finding a stain in man" (Eccl 7:20; Prov 24:16). In order that nothing of this sort may occur to the soul of a person who would approach God in prayer, the Divine Word di- rects that we should not look at our achievements. Rather, we should constantly be mindful of human- ity's common debts in which every supplicant himself necessarily participates by being part of humanity, and should plead with the Judge to grant us release from offenses.

Adam in Us

Adam, it would seem, still lives in us. We see our nature in every generation clothed with the garments of skin (Gen 3:21) and covered with the temporary leaves of this material life that we have badly sewn together (Gen 3:7), after having been stripped of our own radiant garments. Instead of the divine vesture, we have been clothed with luxuries, human glories, temporal honors and fleeting com- forts of the flesh. Until now we continue to behold the realm of the flesh where we have been con- demned to sojourn.

If we look to the East when we pray, it is not because we contemplate God only there. God is everywhere, containing all things. He is not to be found uniquely in any particular place. It is rather be- cause our first homeland was in the East, I mean our way of life in paradise from which we have fallen. For "God planted paradise in Eden towards the East" (Gen 2:8).

When we look to the East, we bring to mind our fall from the luminous regions of bliss in the East. It is therefore appropriate that we should offer this petition for we live in the shadow of the evil fig tree of this life. We have been cast away from the eyes of God. We have willingly defected to the snake which crawls on the ground and eats earth. It slithers on its chest and belly, and counsels us to do the same by seeking earthly delights. It leads our hearts to grovel in base thoughts. It directs us to crawl on our belly, that is, to be preoccupied with the life of pleasure.

Living in these conditions we are like the prodigal son who endured the long toil of tending to the swine. When we, as he did, come to our senses and remember the heavenly Father, we do well to pray the words: "Forgive us our debts." Whether one is another Moses or Samuel, or anyone else who has excelled in virtue, he should in no way think that this petition is less appropriate for himself. He, too, is human, sharing in Adam's nature and consequently sharing in the Fall. Since the Apostle says, "in Adam we all die" (I Cor 15:22), the words of repentance appropriate to Adam are also suited to all those who died with him. Thus, by being granted forgiveness of sin, we in turn may be saved by grace, as the Apostle says (Eph 2:5).

The Testimony of Conscience

All the above has been stated so that, after reviewing the more general concept, we may reflect on the following notion. If anyone seeks the true meaning of this petition for forgiveness, I do not think it necessary for us to apply its meaning simply to the reality of our common nature; because what each has done in his own life, according to the testimony of conscience, is sufficient to make the plea for mercy necessary. Life in this world is lived in many forms involving the soul and mind, as well as the bodily senses. It is difficult, if not altogether impossible, for anyone not to succumb to some sinful pas- sion.

What I mean is this. The pleasurable life of the body has to do with the various senses, whereas the life of the soul is regarded as the activity of the mind and the movement of free will. Who is so lofty in character and noble in thought as to be entirely free from the stain of evil in both realms? Whose eyes are sinless? Whose ears are without guilt? Whose mouth has not tasted the brutish pleasure of food? Whose sense of touch is pure from sin?

Is there anyone who does not know the symbolic meaning of Scripture's words, "Death has en- tered through the windows" (Jer 9:21)? For Scripture calls "windows" the senses through which the soul moves toward external things and grasps whatever it likes. These windows, according to the Divine Word, make a path for the entry of death.

Indeed, the eye is often the entry of numerous spiritual deaths. A person sees another who is angry and is himself aroused to the same sinful passion. Or he observes another prospering undeserv- edly and is inflamed by envy. Or he notices another behaving arrogantly and yields to hatred. Or, seeing a colorful item or a beautifully shaped form, he is overcome by the desire for the pleasing object. In the same way the ear also opens the windows to the entry of death. By means of what it hears, it admits many passions into the soul, such as fear, sorrow, anger, sinful pleasure, evil desire, uncontrolled laugh- ter and the like.

Moreover, the experience of pleasure is, one could say, the mother of all particular evils. Who does not know that in daily conduct the preoccupation with satisfying the palate is virtually the root of all offenses? For on this depend luxury, drunkenness, gluttony, culinary prodigality, wasteful abundance, satiety, reveling, and brutish indulgence to irrational and shameful passions. Similarly, the sense of touch is also the agent of the worst sins. For whatever things pleasure seekers contrive to satisfy the body, are but diseased symptoms of the sense of touch. Of these it would take too long to speak and, in any case, it would be unseemly to mix the dignified aspects of our discourse with all the offenses counted against the sense of touch.

And who could possibly enumerate the moral failures of the soul and free will? "From within," Christ says, "proceed evil thoughts" and added the entire list of deliberations which defile us (Mt 15:18-19). If therefore the webs of sin are spread all around us through the senses and the inward impulses of the soul, "who can boast ' " as Wisdom says, "that his heart is pure" (Prov 20:9)? Or as Job likewise testifies, "Who is pure from filth" (job 14:4)? The filth that defiles the soul's purity is the love of pleasure which is mixed in many and various ways with human life by means of both the body and soul, that is, through the deliberations of the mind, the physical senses, the movements of free will, and the actions of the body.

Whose soul is therefore pure from the blemish of the love of pleasure? Who has not been as- saulted by vanity or has not succumbed to pride? Whose sinful hands have not caused him to waver or whose feet have not made him run to evil? Who has not been defiled by a roving eye or has not been polluted by an undisciplined ear? Whose palate has not been preoccupied with its pleasures or whose heart has not been stirred by vain impulses? All these human failings appear worse and more irksome among more brutish people. However, all those who share the same nature necessarily share the failings of that same nature as well. It is for this reason that we bow before God in prayer and beseech Him to forgive our debts.

Physician Heal Thyself

But such a plea is fruitless, even if it reaches the hearing of God, unless the conscience cries out jointly with us that it is good to share mercy with others. A person rightly judges that love of humanity properly belongs to God. If he thought otherwise, he would not bother to seek something improper and unsuitable to God's nature. The same person, then, is just when confirming his judgment about what is good by his own actions. In that way, he may not hear the Judge say words such as, "Physician, heal yourself" (Lk 4:23). Do you ask me to show love for humanity which you yourself did not share with your neighbors? Do you request forgiveness of debts, when you strangle your debtor?

You pray that God will wipe away your recorded debts, but you yourself carefully preserve the contracts of those indebted to you. You ask for your debts to be canceled, but you enlarge the loan through interest. While your debtor is in prison, you dare come to the place of prayer. He suffers on ac- count of his debts to you, but you deem it right that your own debt should be forgiven. Your prayer can- not be heard because the voice of the sufferer overcomes it. If you cancel the material debt, the bonds of your soul will be loosened. If you forgive, you will be forgiven. Be your own judge, your own lawgiver. By your disposition to your debtor, you bring on yourself the same sentence from above.

It seems to me that the Lord teaches the same truth in another place by means of a parable (Mt 18:23-34). According to the story, a king sat on his fearful throne and brought his servants to trial, seek- ing to know from each how they managed their affairs. One of the debtors who was brought before him received the benefit of the king's loving kindness because he fell at his feet and, instead of payment of the money, he offered a supplication. However, when he later showed an exacting and cruet disposition toward a fellow servant over a small debt, he angered the king because of his cruelty toward his fellow servant. The king then commanded the jailers to cast him completely out of the king's house and to ex- tend the punishment until the penalty was fully paid. It is indeed true that the debts owed to us by our brothers are like a few insignificant coins as compared to myriads of money, that is, our own offenses against God.

Dealing with Difficult People

Of course the insulting behavior of someone, or the wickedness of a servant, or even a threat of physical death, are hurtful. But then, desiring to take revenge, your heart burns with anger and you seek to contrive every means by which to punish those who caused you grief. You do not stop to think, when you are inflamed with anger against your servant, that it is not nature itself but a tyrannical power that has divided humanity into slaves and masters. For the Master of the universe legislated that only the dumb creatures should serve man, as the Prophet David says: "You have put all things under his feet, all sheep and oxen, the birds and beasts and fish" (Ps 8:68). Such creatures He calls servants according to another prophecy: "He gives to the beasts their food and grass for the service of human beings" (Ps 147:9; 104:14). But man He has endowed with the grace of free will. Therefore he, who is subject to you by custom and law, is equal to you by natural right. He is neither created by you, nor has his life in you, nor has received from you his physical and spiritual energies.

Why then do you burn with anger against a servant who has been lazy at work, or has shirked it, or perhaps has shown disdain to your face? Should you not rather look at yourself and how you have behaved toward the Master who created you and brought you into existence, making you a sharer of the world's wonders? He has established the sun for your enjoyment and has granted you all the necessary means to live from the elements of nature-earth, fire, air and water. He has endowed you with the gift of reason, the sense perception, and the knowledge to discern between good and evil.

To what extent have you been obedient and blameless before such a Master? Have you not shirked from His lordship? Have you not run away to sin? Have you not exchanged His lordship with that of evil? Have you not, as far as it was up to you, left the Master's house deserted and run away from the duties you were set to work and guard? Think about all these offenses which ought not to occur. Do you not commit them either by deed or speech or thought, right under they eye of the omnipresent God as witness?

Therefore, if you have behaved in this manner and are a debtor regarding so many things, do you consider it a great matter to give your fellow servant some leeway, or to overlook some offense of his against you? If we are to bring before God our entreaty for mercy and forgiveness, let us first cultivate the confidence of conscience by presenting our life as advocate of our petition and then truly say, "as we, too, have forgiven our debtors."

About Temptations and the Evil One

What does the next petition mean? It is necessary, I think, not to leave this petition unexamined. Knowing about what we are praying, let us make our entreaty with the soul and not the body: "Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from the Evil One."

Beloved, what is the meaning of these words? It seems to me that the Lord names the Evil One by many and various titles according to the variations of evil operations. He calls him by many names such as Devil, Beeizebul, Mammon, ruler of the world, murderer of man, Evil One, father of lies, and other similar names.

Therefore "temptation" is perhaps a sort of name for one of his activities. My suggested meaning is confirmed by the structure of the petition. For, having said, "lead us not into temptation," He adds the clause "to be delivered from the Evil One," as if He means the same thing by both references. He who has not entered into temptation is wholly removed from the Evil One and he who has succumbed to temptation is necessarily under the influence of the Evil One. Therefore both temptation and the Evil One bear one and the same meaning.

What then does this teaching of the prayer commend to us? To detach ourselves from the affairs of this world because "the whole world is in the power of the Evil One" (I jn 5:19). Whoever therefore wants to be removed from the Evil One must necessarily withdraw himself from the world. For tempta- tion has no handle on the soul except by way of enticing the more covetous through worldly preoccupa- tion, as if through bait on the hook of evil.

Let me make this meaning perhaps clearer by other examples. A sea storm is often dangerous, but never to those who live far from it. Fire is destructive, but only to the material it grasps. War is terri- ble, but only for those arrayed for battle. Whoever wants to escape the evil misfortunes of war prays not to be entangled in it. Whoever fears fire trusts not to be caught in it. He who shudders at the sight of the sea hopes not to have to make a voyage. So also, he who fears the assault of the Evil One prays not to come under his influence. As we have said, according to the Lord, the world is in the power of the Evil One. The causes of temptations arise from worldly preoccupations. Therefore he who prays to be deliv- ered from the Evil One does well to entreat to be removed from temptations. For no one would swallow the hook, if he did not first covet to grasp the bait.

But let us stand and say to God: "Lead us not into temptation," that is, into the evils of daily life, but deliver us from the Evil One" who possesses power over this world. May we then be delivered from the evil one by the grace of Christ, to whom belongs the power and the glory, together with the Father and the Holy Spirit, now and forever, and to the ages of ages. Amen.