Jesus Prayer - Breathing Exercises

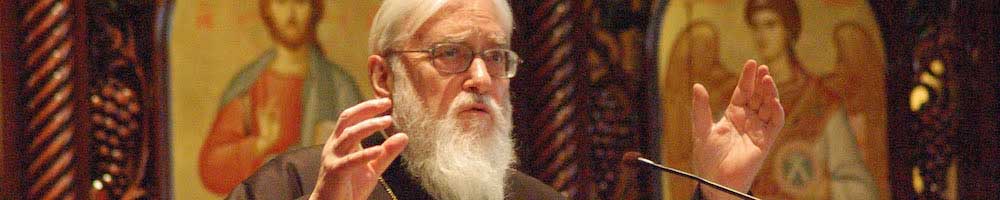

by Bishop Kallistos-WareIt is time to consider a controversial topic, where the teaching of the Byzantine Hesychasts is often misinterpreted — the role of the body in prayer.

The heart, it has been said, is the primary organ of our being, the point of convergence between mind and matter, the centre alike of our physical constitution and our psychic and spiritual structure. Since the heart has this twofold aspect, at once visible and invisible, prayer of the heart is prayer of body as well as soul: only if it includes the body can it be truly prayer of the whole person. A human being, in the biblical view, is a psychosomatic totality — not a soul imprisoned in a body and seeking to escape, but an integral unity of the two. The body is not just an obstacle to be overcome, a lump of matter to be ignored, but it has a positive part to play in the spiritual life and it is endowed with energies that can be harnessed for the work of prayer.

If this is true of prayer in general, it is true in a more specific way of the Jesus Prayer, since this is an invocation addressed precisely to God Incarnate, to the Word made flesh. Christ at his Incarnation took not only a human mind and will but a human body, and so he has made the flesh into an inexhaustible source of sanctification. How can this flesh, which to God-man has made Spirit-bearing, participate in the Invocation of the Name and in the prayer of the intellect in the heart?

To assist such participation, and as an aid to concentration the Hesychasts evolved a ‘physical technique’. Every psychic activity, they realized, has repercussions on the physical and bodily level; depending on our inner state we grow hot or cold, we breathe faster or more slowly, the rhythm of our heart-beats quickens or decelerates, and so on. Conversely, each alteration in our physical condition reacts adversely or positively on our psychic activity. If, then, we can learn to control and regulate certain of our physical processes, this can be used to strengthen our inner concentration in prayer. Such is the basic principle underlying the Hesychast ‘method’. In detail, the physical technique has three main aspects:

i) External posture. St Gregory of Sinai advises sitting on a low stool, about nine inches high; the head and shoulders should be bowed, and the eyes fixed on the place of the heart. He recognizes that this will prove exceedingly uncomfortable after a time. Some writers recommend a yet more exacting posture, with the head held between the knees, following the example of Elijah on Mount Carmel.

ii) Control of the breathing. The breathing is to be made slower and at the same time co-ordinated with the rhythm of the Prayer. Often the first part, ‘Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God’, is said while drawing in the breath, and the second part, ‘have mercy on me a sinner’, while breathing out. Other methods are possible. The recitation of the Prayer may also be synchronized with the beating of the heart.

iii) Inward exploration. Just as the aspirant in Yoga is taught to concentrate his thought in specific parts of his body, so the Hesychast concentrates his thought in the cardiac centre. While inhaling through his nose and propelling his breath down into his lungs, he makes his intellect ‘descend’ with the breath and he ‘searches’ inwardly for the place of the heart. Exact instructions concerning this exercise are not committed to writing for fear they should be misunderstood; the details of the process are so delicate that the personal guidance of an experienced master is indispensable. The beginner who, in the absence of such guidance, attempts to search for the cardiac centre, is in danger of directing his thought unawares into the area which lies immediately below the heart — into the abdomen, that is and the entrails, the effect on his prayer is disastrous, for this lower region is the source of the carnal thoughts and sensations which pollute the mind and the heart.

For obvious reasons the utmost discretion is necessary when interfering with instinctive bodily activities such as the drawing of breath or the beating of the heart. Misuse of the physical technique can damage someone’s health and disturb his mental equilibrium; hence the importance of a reliable master. If no such starets is available, it is best for the beginner to restrict himself simply to the actual recitation of the Jesus Prayer, without troubling at all about the rhythm of his breath or his heart-beats. More often than not he will find that, without any conscious effort on his part, the words of the Invocation adapt themselves spontaneously to the movement of his breathing. If this does not in fact happen, there is no cause for alarm; let him continue quietly with the work of mental invocation.

The physical techniques are in any case no more than an accessory, an aid which has proved helpful to some but which is in no sense obligatory upon all. The Jesus Prayer can be practised in its fullness without any physical methods at all. St Gregory Palamas (1296-1359), while regarding the use of physical techniques as theologically defensible, treated such methods as something secondary and suited mainly for beginners. For him, as for all the Hesychast masters, the essential thing is not the external control of the breathing but the inner and secret Invocation of the Lord Jesus.

Orthodox writers in the last 150 years have in general laid little emphasis upon the physical techniques. The counsel given by Bishop Ignatii Brianchaninov (1807-67) is typical:

We advise our beloved brethren not to try to establish this technique within them, if it does not reveal itself of its own accord. Many, wishing to learn it by experience, have damaged their lungs and gained nothing. The essence of the matter consists in the union of the mind with the heart during prayer, and this is achieved by the grace of God in its own time, determined by God. The breathing technique is fully replaced by the unhurried enunciation of the Prayer, by a short rest or pause at the end, each time it is said, by gentle and unhurried breathing, and by the enclosure of the mind in the words of the Prayer. By means of these aids we can easily attain to a certain degree of attention.

As regards the speed of recitation, Bishop Ignatii suggests:

To say the Jesus Prayer a hundred time attentively and without haste, about half an hour is needed, but some ascetics require even longer. Do not say the prayers hurriedly, one immediately after another. Make a short pause after each prayer, and so help the mind to concentrate. Saying the Prayer without pauses distracts the mind. Breathe with care, gently and slowly.

Beginners in the use of the Prayer will probably prefer a somewhat faster pace than is here proposed — perhaps twenty minutes for a hundred prayers. In the Greek tradition there are teacher who recommend a far brisker rhythm; the very rapidity of the Invocation, so they maintain, helps to hold the mind attentive.

Striking parallels exist between the physical techniques recommended by the Byzantine Hesychasts and those employed in Hindu Yoga and in Sufism. How far are the similarities the result of the mere coincidence, of an independent though analogous development in two separate traditions? If there is a direct relation between Hesychasm and Sufism — which side has been borrowing from the other? Here is a fascinating field for research, although the evidence is perhaps too fragmentary to permit any definite conclusion. One point, however, should not be forgotten. Besides similarities, there are also differences. All pictures have frames, and all picture-frames have certain features in common; yet the pictures within the frames may be utterly different. What matters is the picture, not the frame. In the case of the Jesus Prayer, the physical techniques are as it were the frame, while the mental invocation of Christ is the picture within the frame. The ‘frame’ of Jesus Prayer certainly resembles various non-Christian ‘frames’, but this should not make us insensitive to the uniqueness of the picture within, to the distinctively Christian content of the Prayer. The essential point in the Jesus Prayer is not the act of repetition in itself, not how we sit or breathe, but to whom we speak; and in this instance the words are addressed unambiguously to the Incarnate Saviour Jesus Christ, Son of God and Son Mary.

The existence of a physical technique in connection with the Jesus Prayer should not blind us as to the Prayer’s true character. The Jesus Prayer is not just a device to help us concentrate or relax. It is not simply a piece of ‘Christian Yoga’, a type of ‘Transcendental Meditation’, or a ‘Christian mantra’, even though some have tried to interpret it in this way. It is, on the contrary, an invocation specifically addressed to another person — to God made man, Jesus Christ, our personal Saviour and Redeemer. The Jesus Prayer, therefore, is far more than an isolated method or technique. It exists within a certain context, and if divorced from that context it loses its proper meaning.

The context of the Jesus Prayer is first of all one of faith. The Invocation of the Name presupposes that the one who says the Prayer believes in Jesus Christ as Son of God and Saviour. Behind the repetition of a form of words there must exist a living faith in the Lord Jesus — in who he is and in what he has done for me personally. Perhaps the faith in many of us is very uncertain and faltering; perhaps it coexists with doubt; perhaps we often find ourselves compelled to cry out in company with the father of the lunatic child, ‘Lord, I believe: help my unbelief’ (Mark 9:24). But at least there should be some desire to believe; at least there should be, amidst all the uncertainty, a spark of love for the Jesus whom as yet we know so imperfectly.

Secondly, the context of the Jesus Prayer is one of community. We do not invoke the Name as separate individuals, relying solely upon our own inner resources, but as members of the community of the Church. Writers such as St Barsanuphius, St Gregory of Sinai or Bishop Theophan took it for granted that those to whom they commended the Jesus Prayer were baptized Christian, regularly participating in the Church’s sacramental life through Confession and Holy Communion. Not for one moment did they envisage the Invocation of the Name as a substitute for the sacraments, but they assumed that anyone using it would be a practising and communicant member of the Church.

Yet today, in this present epoch of restless curiosity and ecclesiastical disintegration, there are in fact many who use the Jesus Prayer without belonging to any Church, possibly without having a clear faith either in the Lord Jesus or anything else. Are we to condemn them? Are we to forbid them the use of the Prayer? Surely not, so long as they are sincerely searching for the Fountain of Life. Jesus condemned no one except hypocrites. But, in all humility and acutely aware of our own faithlessness, we are bound to regard the situation of such people as anomalous, and to warn them of this fact.

Back to main article Next (Journey's End)